Crime fiction and literary punishment

Finishing “The Paris Review Interviews, Volume II” this week got me thinking about the separation—chasm really—that grew between literary and pop fiction in the middle of the last century. The thoughts bubbled up, in fact, after reading the interview with the late Philip Larkin, giant of 20th Century poetry.

Finishing “The Paris Review Interviews, Volume II” this week got me thinking about the separation—chasm really—that grew between literary and pop fiction in the middle of the last century. The thoughts bubbled up, in fact, after reading the interview with the late Philip Larkin, giant of 20th Century poetry.

Larkin was asked what he read. “Books I’m sent to review. Otherwise novels I’ve read before. Detective stories: Gladys Mitchell, Michael Innes, Dick Francis.”

Detective stories? So this literary giant—the author of my favorite modern poem, “This Be The Verse”—picked up one of Dick Francis’s racetrack whodunits when he kicked back. He wasn’t the only one from the literary big leagues who liked a mystery. I read once William Faulkner usually had a crime novel on his nightstand.

Aren’t these the kinds of things we crime writers want (need?) to hear? We want to be taken seriously by the literary establishment folks. I’ve heard many a genre writer call for a healing of the rift between literary and popular, so we all can be Dickens. Let’s face it, that’s not going to happen.

You write what you imagine. It’s starts there, always and everywhere, not with a theory or a psychology or an ideology. You don’t chose to be Faulkner or Francis. You can try, of course. And that way lies awful writing.

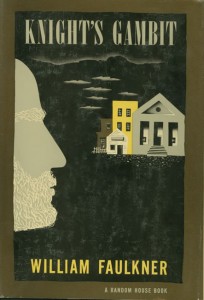

I went Interneting this afternoon to confirm that Faulkner nightstand anecdote. I couldn’t find it. Instead, I came on something even better in the web archive of the J.D. Williams Library at Ole Miss. Faulkner actually wrote detective fiction, something I didn’t know but probably should have. In 1946, his story “An Error in Chemistry” took second place in a short-story competition run by Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. The story was then included in “Knight’s Gambit,” a collection of six mysteries featuring lawyer Gavin Stevens published in 1949. That was the very same year Faulkner won another prize—the Nobel for Literature. Can you imagine a Nobel winner ever again putting out a bunch of detective stories right as she or he were jetting off to Stockholm? The gulf between the popular, the accessible, the commercial and the literary, the difficult, the art grows wider every year. (Faulkner also slummed in Hollywood, writing the screenplay for the film of Raymond Chandler’s novel “The Big Sleep.” When do think Thomas Pynchon will be taking a writing gig with Spielberg’s company?)

The Ole Miss library is a little treasure drove on Faulkner and crime. It has on loan from the late author’s own library vintage paperbacks he collected, including books by Erle Stanley Gardner, Rex Stout, Eric Ambler and Agatha Christie. I imagine Faulkner and Larkin arguing the merits of Rex Stout and Dick Francis. And Chandler barging into the room—with a gun, to follow his own prescription—to tell them in blunt terms how wrong they both are. And why. Would we learn more from that than the deconstructions of the college profs? I don’t know. It would certainly be more fun.

Maybe, that’s my problem. I just want to have fun. No, that’s too glib. I stand by what I said above. I can only write what I imagine. Imagination comes before everything else. It is what produces the stories, and the language I use. It was the same for Larkin and Faulkner and Francis and Stout. It would have been nice to have been born with Faulkner’s imagination. Alas, I was not. I’ll just have to hope one of my stories ends up on the nightstand of Doris Lessing or Tomas Tranströmer.

Yeah, I know. In my dreams. But that’s what it’s about after all. Dreams.