Them, Robots

Morgan is a great airplane movie. I had no plans to see it when it came out. My expectations were set quite low on a flight last week. It jumped that low bar and gave me some things to think about. Before the thinking, the movie: things are going mighty wrong in the effort to create a fake human (synth, android, robot, pick your poison). Right at the beginning, synthetic human Morgan, looking about 15, but real age five (she’s a fast grower), stabs a caretaker in the eye.

Morgan is a great airplane movie. I had no plans to see it when it came out. My expectations were set quite low on a flight last week. It jumped that low bar and gave me some things to think about. Before the thinking, the movie: things are going mighty wrong in the effort to create a fake human (synth, android, robot, pick your poison). Right at the beginning, synthetic human Morgan, looking about 15, but real age five (she’s a fast grower), stabs a caretaker in the eye.

Things are going to get worse. You can tell. Particularly once we figure out this is a movie trotting out the old trope (or cliche, you choose) about building fake humans (synths, robots) to be soldiers. More precisely, weapons. I won’t ruin the end, in case you’re on plane sometime soon.

My thinking:

- An entire category of movies and TV shows would disappear if the imaginary robot/android/synth/fake-life manufacturing industry followed Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics. I mean, why would you not put in Law 1? “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” The Amazon series “Humans” nods at the law, then walks around it. A character talks about overriding the Asimov protocols in a synth. That. Should. Not. Be. Possible. For a safe society, at least, though boring robot movies.

- My next thought, as the movie ground toward its pretty inevitable conclusion, was about how indignant Isaac Asimov was when his laws were not programmed into Hal 9000, the computer aboard the ship in 2001: A Space Odyssey. There was a great exchange between Asimov and 2001 author Arthur C. Clarke, but I can’t find it anywhere on my interwebs. Suffice it to say, Clarke felt he could do what he wanted in his universe. I’ve not read that Asimov protested the hundreds of TV shows and movies after that ignored his Three Laws of Robotics–probably realizing it would do little good. Thus was born a mighty industry making filmed entertainment about deadly robot-android-synths.

- But really, why bother making the movie Morgan when the best film about synthetic human soldiers, Blade Runner, has been around for decades. The banal Morgan dialogue was replaced in my head by Rutger Hauer as Roy, speaking his dying words. “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

- Credits rolled at the end Morgan, and I got an answer to No. 3. The director of the film was Todd Scott. I start wondering. Up comes the executive producer, Ridley Scott. Interweb confirms Todd’s the son of the director of Blade Runner. Not only are deadly robot-android-synth movies and shows an industry, they’re a family business.

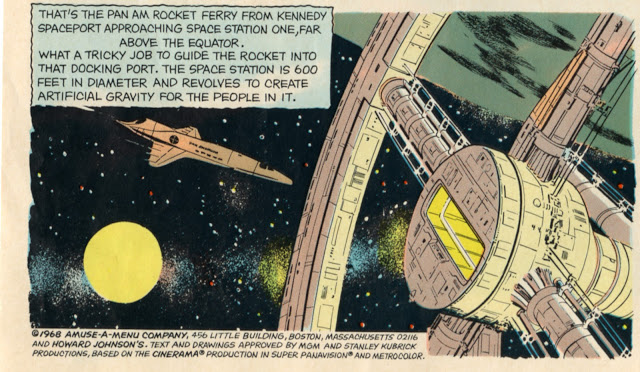

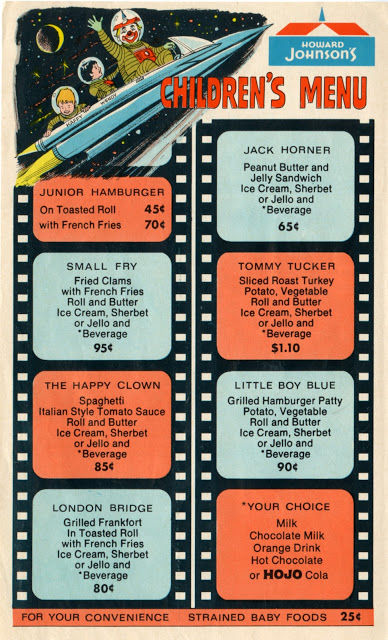

Collisions that happen in my mind: “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Interstellar” and Howard Johnson. Okay, the first two are obvious for the way the first movie informed the second. (How many “2001” references did you count in “Interstellar”?)

Collisions that happen in my mind: “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Interstellar” and Howard Johnson. Okay, the first two are obvious for the way the first movie informed the second. (How many “2001” references did you count in “Interstellar”?)

Downtown Ticonderoga has its fair share of boarded up shops and closed buildings. The present day reality for the town is the recession hasn’t been very good for the tourist grade. But it also has Burleigh’s Luncheonette, a place that truly deserves to be called luncheonette, emphasis on “ette.” Half of Burleigh’s is taken up by the classic luncheonette counter, really two U-shaped counters built to maximize seating. One row of booths runs along the wall opposite. The place is what it always has been, but also recognizes that it is retro. There are old bikes hanging from the ceiling, copies of hand-typed menus from decades ago and a jukebox loaded with singles. Unlike restaurants dressed up to play the old-time part, Burleigh’s has been presiding over downtown Ti (as locals call it) for a very long time.

Downtown Ticonderoga has its fair share of boarded up shops and closed buildings. The present day reality for the town is the recession hasn’t been very good for the tourist grade. But it also has Burleigh’s Luncheonette, a place that truly deserves to be called luncheonette, emphasis on “ette.” Half of Burleigh’s is taken up by the classic luncheonette counter, really two U-shaped counters built to maximize seating. One row of booths runs along the wall opposite. The place is what it always has been, but also recognizes that it is retro. There are old bikes hanging from the ceiling, copies of hand-typed menus from decades ago and a jukebox loaded with singles. Unlike restaurants dressed up to play the old-time part, Burleigh’s has been presiding over downtown Ti (as locals call it) for a very long time. The last stop on this trip was Great Escape and Splashwater Kingdom, a Great Adventures theme park outside the Village of Lake George. This was like visiting an archeological dig of my own childhood. You see, Great Escape was built on top of Storytown USA, which, in turn, was a homely little amusement park opened in 1954 (pre-dating Disneyland by a year). My family visited Storytown during the seventies. It was our trip to Disney. If you look carefully under the roller coasters and other new rides, you’ll see signs and scenes from the original park left in place to keep the connection. I took the steam train ride—it also looked unchanged—and chugged by a storybook house, vintage Storytown USA signs and a smiling purple dragon.

The last stop on this trip was Great Escape and Splashwater Kingdom, a Great Adventures theme park outside the Village of Lake George. This was like visiting an archeological dig of my own childhood. You see, Great Escape was built on top of Storytown USA, which, in turn, was a homely little amusement park opened in 1954 (pre-dating Disneyland by a year). My family visited Storytown during the seventies. It was our trip to Disney. If you look carefully under the roller coasters and other new rides, you’ll see signs and scenes from the original park left in place to keep the connection. I took the steam train ride—it also looked unchanged—and chugged by a storybook house, vintage Storytown USA signs and a smiling purple dragon.