Archive for the ‘the future’ Category

Train posters worth stealing, part 1

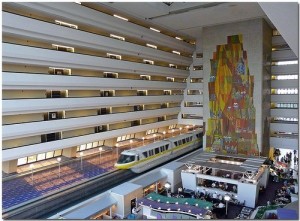

Monorail ride to the future past

Walt Disney spoke from the TV: “We call it EPCOT. Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow.” I sat cross-legged on the floor of our basement rec room (what family rooms were called once, in the age before flat-screens, Playstation and great rooms). Walt was taking ten-year-old me — me personally — through his plans for Walt Disney World. Of all the things that caught my fancy, the thing I ached to visit most was the Contemporary Resort Hotel, the giant A-frame with the monorail that ran right into its Grand Canyon Concourse lobby.

The hotel and monorail were something out of the science fiction books I read then, like something right off one of the covers. I honestly can’t remember any of the theme park rides Walt talked about, but I do remember the monorail zipping silently into the hotel.

Walt Disney spoke again from the TV. They were the same words, the same clips. But it was earlier this week, and I was on the bus from the airport to Disney World for our stay at The Contemporary. Few things survive four decades of wanting. The hotel and the monorail are now a vision of the future from the past, a vision of future past, if you will. But as late I arrived to the place, I loved every minute of my stay, perhaps as much as the aching ten-year-old would have.

Walt Disney spoke again from the TV. They were the same words, the same clips. But it was earlier this week, and I was on the bus from the airport to Disney World for our stay at The Contemporary. Few things survive four decades of wanting. The hotel and the monorail are now a vision of the future from the past, a vision of future past, if you will. But as late I arrived to the place, I loved every minute of my stay, perhaps as much as the aching ten-year-old would have.

The rooms were a little beat on — chips in the finish here and there — from wear and tear since 1971, but they were still a sleek, clean-lined vision of what living the day after tomorrow was supposed to look like. A mosaic of glass covered the area where the fireplace should be, and a light switch created a glimmering, smoke-free hearth. The desk with its separate, elliptical table for a laptop was as serviceable a hotel workstation as I’d ever used, and the individual spotlights in the ceiling above the beds the best reading lamps.

I met a man during my stay who said that when he brought his dad to Disney World for the first time, all the father wanted to do was ride the monorail. So he did. I understood that desire.

EPCOT was planned as something akin to a permanent World’s Fair, with pavilions dedicated to different countries and to the exploration of science. World’s Fairs, New York 39 and 64 in particular, conjure up their own images of the past’s view of its happy future. I am now as fascinated with those visions of the future as I am with the future itself. Maybe it’s because I’m getting old, or maybe because the retro-future is as weird as the stories we’re writing now.

It’s easy to be jaded and ironic, snicker even at Walt’s happy visions — all his visions of wishes and dreams and a Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow. Not for me, not looking out across the Grand Canyon Concourse from the eighth floor as the monorail whispered in from the Magic Kingdom.

The Economist is a funny book

This week, I’m only posting things that are funny. Course, they may only be funny to me. A college classmate of mine and I split the cost of an Economist subscription, mainly because we were fascinated with the touted median income of its readers, $92,000 (in 1980!). We figured we’d give that number a knock.

This week, I’m only posting things that are funny. Course, they may only be funny to me. A college classmate of mine and I split the cost of an Economist subscription, mainly because we were fascinated with the touted median income of its readers, $92,000 (in 1980!). We figured we’d give that number a knock.

I get it now out of pretense, for the two articles I read a week and the covers. Here’s this week’s, on the Facebook IPO, and funnier than any of the snark-books will manage.

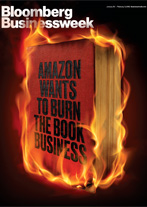

Real books sold, book business burned

Every writer probably spends some time wondering what form the “book” she is writing will take and how it will get out into the world of readers. Like many, I’m resigned to a future filled with e-books, though really really want a real book to hold if I’m ever published. At least my first one, for the immortality bits and bytes can never confer. There’s a reason “the cloud” is now the preferred name for the place where all our digital stuff goes to live. Clouds are emphemeral.

Publisher’s Lunch reported heartening news after the holidays for those of us who want to hold a book, any book. The publishing newsletter covered Barnes & Noble’s pretty decent holiday sales, noting the retail chain said, “book sales were strong overall, fueled by strength across multiple categories,” and “physical book sales on a comparable basis increased by 4 percent, exhibiting growth for the first time in five years.”

Publisher’s Lunch reported heartening news after the holidays for those of us who want to hold a book, any book. The publishing newsletter covered Barnes & Noble’s pretty decent holiday sales, noting the retail chain said, “book sales were strong overall, fueled by strength across multiple categories,” and “physical book sales on a comparable basis increased by 4 percent, exhibiting growth for the first time in five years.”

For the radical take, look to Bloomberg Businessweek’s excellent cover story this week, “Amazon Wants to Burn the Book Business.” Brad Stone’s piece details Amazon’s push into book publishing. This is not an e-books-only story, as Amazon is arranging to have physical versions printed. This is not an authors-get-screwed story, as writers get a much better split when they do business directly with Amazon. But it is a big-six-publishers-are-in-deep-doo-doo story.

“The reaction to Amazon’s move is analogous to the screech of a small woodland creature being pursued by a jungle predator,” writes Stone in the article. Publishers are “trying to protect a century-old business model—and their role as nurturers of literary culture—from encroachment by a company that consistently reimagines how industries can be run more efficiently. Book publishing, an inefficient industry if there ever was one, seems ripe for reimagining.”

Whether you agree with the article’s take, or Amazon’s strategy, it is must reading for all of us who like to read, and to hold books, whether our own or anyone else’s.

Obsessing on cars in little boxes

The Crossroads in Boulder was the first indoor mall I visited. I was five and we’d just moved from Poughkeepsie, which though already IBM country, was still pretty rural and only had strip shopping centers. The year was 1965. On my first visit, I decided the mall was called the Crossroads because it was like being on two indoor roads that crossed, a giant plus of a building filled with stores. (In reality, it probably got its name from some intersection of two important roads in Boulder.)

At the crossroads of the Crossroads was a toy shop, a smallish store crammed with stuff. The aisles were narrow and the shelves tall (to me). And on one counter sat a glass display case with stepped shelves. Parked on the shelves were miniature cars, Matchbox cars, and these I coveted from my first visit to the Crossroads. I don’t know what they cost then, but I wasn’t often able to buy one. I would stand and stare at the white Cadillac ambulance on visit after visit, needing that car more than I needed anything else in the world. I also wanted, needed the Chevrolet El Camino, though not as badly as the ambulance. Back then, Matchbox cars were made by a company call Lesney, and that also made them special. They were imported. From Britain. Little metal cars that felt heavy, real, constructed somewhere.

At the crossroads of the Crossroads was a toy shop, a smallish store crammed with stuff. The aisles were narrow and the shelves tall (to me). And on one counter sat a glass display case with stepped shelves. Parked on the shelves were miniature cars, Matchbox cars, and these I coveted from my first visit to the Crossroads. I don’t know what they cost then, but I wasn’t often able to buy one. I would stand and stare at the white Cadillac ambulance on visit after visit, needing that car more than I needed anything else in the world. I also wanted, needed the Chevrolet El Camino, though not as badly as the ambulance. Back then, Matchbox cars were made by a company call Lesney, and that also made them special. They were imported. From Britain. Little metal cars that felt heavy, real, constructed somewhere.

The box was the final element that turned them into kid obsession. Once you pointed to the car you wanted — could afford, really — the store clerk would slide open a drawer and pull out the special blue and yellow box with the car in it. The box had the car’s picture and name, and was instant garage for each car — no plastic blister pack here. That’s where the name comes from, though I’ve never seen a matchbox that size, so I assume it must have been the standard in England.

My son Patrick has the sharpest eyes around. His nickname is Eagle-Eyes McDoom. While it’s a given he often spots the things he wants, this is not always the case. The other day he was in Stop ‘n Shop and saw what I’d seen at the Crossroads in 1965: a “Matchbox Lesney Edition.” In a bid to sell quality and nostalgia, Mattel, which owns Matchbox now, is offering vehicles featuring “the classic combination of quality die-cast body and chasis to honor the heritage of the Lesney name.” Patrick bought me one, generous son that he is, a ’56 Cadillac Eldorado. It feels like the old Matchboxes, with a weight and heft today’s mostly plastic cars can’t match. It even came with that classic blue and yellow box. The irony: car and box were packaged together in the blister pack, for there is no display case at Stop ‘n Shop or a clerk to get the little box out of the drawer. I’ve since gone back and grabbed the ’70 Plymouth Cuda Hemi. Now, it they’d only get in the Cadillac ambulance.

Khan Academy is big business

Khan Academy, the best online math site around, got the New York Times treatment this week as the big feature on the front of Business Day. Not sure why it ran in business, except the free site operated as a non-profit should send the mega-education publishers like Pearson running for the hills screaming: “Where’s my business model? I’ve lost my business model!”

SAN JOSE, Calif. — Jesse Roe, a ninth-grade math teacher at a charter school here called Summit, has a peephole into the brains of each of his 38 students.

via Khan Academy Blends Its YouTube Approach With Classrooms – NYTimes.com.

Visiting a newspaper press

Newspaper printing presses are big-machine loud and inky-greasy dirty. Up close, they look like steam-punk contraptions out of an earlier industrial age. And for me, when I first saw one, magic made out of metal.

I’d like to say my reaction stemmed from something philosophical, say based on the realization of the role a free press plays in a democracy. I’d like to have been thinking of a turn on that phrase Woody Guthrie put on his guitar: “This machine kills fascists.”

read the rest of my column at Pelham Elementary Students Hear, Smell and See the Magic in a Newspaper Press – Pelham, NY Patch.

Out of the mouths of techno-babes

The best detail in the New York Times front page story on how Larry Page is remaking Google is this one:

He does not much like e-mail either — even his own Gmail — saying the tedious back-and-forth takes too long to solve problems.

via Google’s Chief Works to Trim a Bloated Ship – NYTimes.com.

Everyone follow Larry. End the back and forth. Solve problems quickly. Get off the damn email.

Steve Jobs and me

Steve Jobs changed my life. I know, I know. You’ve already heard it and from every other journalist on the planet. An entire issue of Bloomberg BusinessWeek turned into instant biography. The cover of the Economist. Articles in the New York Times showing up two Sundays after the man’s death. People and the Poughkeepsie Journal. I expect Showdog Monthly and Boy’s Life to chime in.

Let’s face it. Steve Jobs lived an amazing life that is an incredible story. Americans love the chance of a comeback. (Fitzgerald was wrong; there are second acts in American lives.) And so it’s hard for editors and reporters to stay away.

There is another reason for the attention being paid. Jobs revolutionized journalism, hell all of publishing, long before upending the music, cell phone and consumer electronics industries.

In 1984, I was intrigued by Apple’s slick “1984” TV spot because of the sci-fi look, not the Macintosh computer it introduced. I was two years into my career in journalism, not in the market for a personal computer, and couldn’t afford one anyway. A year later, I was reading a very unslick newspaper trade publication, an ugly magazine that was all text—arcane, jargony text at that—topped by long obtuse headlines in ALL CAPS. The article was about Apple’s Macintosh computer, LaserWriter printer and the Postscript language built into both that this dense piece seemed to be suggesting turned the Macintosh into a typesetting machine. If so, I knew then, this would change everything.

Two or three months later, I bought the earliest Macintosh, a squat, friendly little box with two floppy disc drives (no hard drive yet). My partners and I started the Peekskill Herald using the little thing as our entire production system. And that newspaper would never have happened without the Mac. Paying a job shop to typeset the Herald would have cost twice as much as our actual printing bill. We would have run out of money in weeks.

The Herald was one of the first 20 or so newspapers in the country typeset using the Mac, Microsoft Word 1.0 and layout software called Aldus Pagemaker. Dozens, then hundreds more newspapers and magazines followed, some junking conventional typesetting equipment, while others were startups empowered by the computer that took out a dictator (well, in commercials at least). Desktop publishing was born, a revolution so complete we don’t use the term much anymore. All publishing is done on the desktop. We expect to have 50 or 100 typefaces at our disposal on a home computer and create documents that would have cost hundreds or thousands of dollars in typesetting costs.

Everything that’s happened in my life since 1985 happened because of my experiences co-founding and co-owning a newspaper built on the fundamental technological shift ushered in by Steve Jobs. Not that it was all business. There was the magic. I’m a techie and love to play with all the toys. Being honest, most are a disappointment. Rarely do I switch on a box and feel the magic. That’s why techies are techies. We go from box to box hoping it will happen again.

Switching on the first Mac was a magic moment. Things we take for granted were all new: the mouse that miraculously moved the arrow around the screen. The windows and icons and virtual desktop. A graphical environment rather than c: awaiting our turgid DOS commands.

From 1985 until now, I’ve bought Apple computers to use at home, even during the desert years when Jobs was gone and Apple tried to be a sort-of Microsoft, an almost IBM. I’ve only felt that magic three times since 1985 and Apple was responsible twice more: when I got my iPhone three years ago and the iPad last year. (If you’re wondering about the non-Apple event: 1994, when I first clicked a hyperlink on the world wide web, and the world wide world changed again.)

I’m writing this on the iPad, typing it into the Safari browser, music playing via the iPod app, using open-source blogging software called WordPress that’s all about a graphical interface. Steve Jobs is in all of it.