Music of the Times (and the spheres)

Most days, it’s pretty easy to guess what the New York Times will lead on. That’s because most days, it’s the Democrats yelling at the Republicans yelling at the Democrats… Well, you get the point. And if it’s not that, it’s the obvious big economic report of the day or the obvious major unrest in foreign parts or the obvious natural disaster.

Most days, it’s pretty easy to guess what the New York Times will lead on. That’s because most days, it’s the Democrats yelling at the Republicans yelling at the Democrats… Well, you get the point. And if it’s not that, it’s the obvious big economic report of the day or the obvious major unrest in foreign parts or the obvious natural disaster.

But the top story on Thursday, July 5, was none of those. The day before, physicists announced they’d found the Higgs boson, an elusive subatomic particle the existence of which may (or may not) confirm the key theory on how the universe operates. You probably know this by now, as the story got big coverage all over the place (cover of the Economist, etc). Still in all, running it as the lead story — that’s the top story on the righthand side of page 1— made the New York Times look science fictional.

Staff writer Dennis Overby rose to the occasion, pulling out all the stops in writing this oddest of top stories. I’m going to quote a bunch of it, because you almost never read prose like this in the lead story of the Times. To wit:

Like Omar Sharif materializing out of the shimmering desert as a man on a camel in “Lawrence of Arabia,” the elusive boson has been coming slowly into view since last winter, as the first signals of its existence grew until they practically jumped off the chart.

He and others said that it was too soon to know for sure, however, whether the new particle is the one predicted by the Standard Model, the theory that has ruled physics for the last half-century. The particle is predicted to imbue elementary particles with mass. It may be an impostor as yet unknown to physics, perhaps the first of many particles yet to be discovered.

That possibility is particularly exciting to physicists, as it could point the way to new, deeper ideas, beyond the Standard Model, about the nature of reality.

The nature of reality? Wow. And Overby was just getting warmed up. Read on for the rock-show ovation, a rendezvous with destiny, and even what it takes to become a bill in Congress (a faint delicious echo of School House rock):

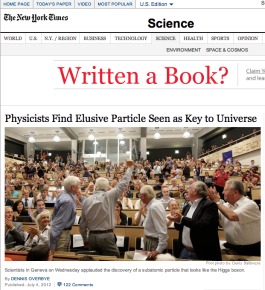

In Geneva, 1,000 people stood in line all night to get into an auditorium at CERN, where some attendees noted a rock-concert ambience. Peter Higgs, the University of Edinburgh theorist for whom the boson is named, entered the meeting to a sustained ovation.

Confirmation of the Higgs boson or something very much like it would constitute a rendezvous with destiny for a generation of physicists who have believed in the boson for half a century without ever seeing it. The finding affirms a grand view of a universe described by simple and elegant and symmetrical laws — but one in which everything interesting, like ourselves, results from flaws or breaks in that symmetry.

According to the Standard Model, the Higgs boson is the only manifestation of an invisible force field, a cosmic molasses that permeates space and imbues elementary particles with mass. Particles wading through the field gain heft the way a bill going through Congress attracts riders and amendments, becoming ever more ponderous.

Gerald Guralnik, one of the founders of the Higgs theory, said he was glad to be at a physics meeting “where there is applause, like a football game.

Yay applause! Yay Higgs! Yay boson! Yay physics! Yay physicists. Yay the New York Times for delivering surprising writing on a surprising story.